Art historian Katy Siegel discussed her recent exhibition at the Rose Art Museum and publication “The heroine Paint”: After Frankenthaler with Gagosian Gallery’s Alison McDonald.

July 14, 2015

The exhibition you curated for the Rose Art Museum, "Pretty Raw: After and Around Helen Frankenthaler," positioned Frankenthaler as “a lens through which to refocus a vision of modernist art over the past sixty years.” What are some examples of the way this idea surfaced throughout the exhibition?

It began with an account of the 1950s as “inclusive and generous,” to borrow Frank O’Hara’s take on how Frankenthaler embodied the spirit of that moment. Taking that spirit as the guiding light for the show, what emerges again and again is decoration, pleasure, and the everyday, along with gender and sexuality. The power and positivity of these threads become stronger throughout the course of the show. These qualities were once seen in a negative light, or as something to conceal, but by the end of the show they become positive, desired by artists and society.

What was it that initiated your interest in this project?

The wish to understand the very real content and passion behind contemporary art that can often be easily dismissed as “light” or decorative. Some of the same critical prejudices that oppose pleasure and play to intellectual or political seriousness persist today. Those prejudices are historical and they are wrong; they prevent us from really seeing.

Did anything about your thinking change during the exhibition planning and installation?

It was fascinating to realize how directly the feminine sensibility, which was a negative critical category in the 1950s, turned into a positive attribute, one to be cultivated, for artists like Lynda Benglis, Miriam Schapiro, and Faith Wilding. I had not realized how direct and historical the connection was between what had been called lyrical or formalist painting and subsequent feminist work.

What are some of your favorite responses to the exhibition?

My favorite responses are the mutual surprise and recognition between people who know

the 1950s work well but were unaware of the contemporary art that reflects some of the same attitudes, and the people deeply engaged with contemporary art who don’t know the history. Introducing those artists to each other is like introducing long-lost cousins. And in general, it was nice to see the pleasure the artists took from being included in this particular version of history.

How do the exhibition and publication relate to each other and how are they different?

The exhibition was 4,000 square feet, so it has fewer artists! The book allowed me to be more expansive, although there is a lot of overlap between the two. And, as always, an exhibition allowed for physical experience—and this work really was breathtaking in person—while a book,

of course, allows you to spell out histories and ideas as well as include different voices. For example, there are six texts included in the publication that are authored by artists, in addition to six new in-depth essays from prominent scholars. It also includes a lot of great non-art imagery—a visual chronology that includes media imagery—that isn’t in the exhibition.

Both the exhibition and publication cover a time span of over sixty years, from the 1950s through to artists working today. What are some themes that emerged in terms of the progression and development of ideas from each generation?

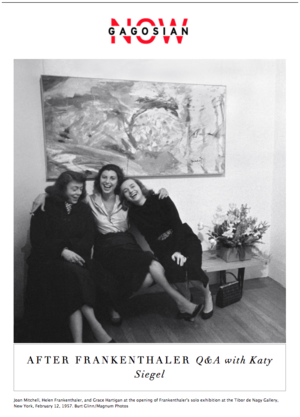

The social quality of art making at different moments, as in the circle around Tibor de Nagy in the 1950s and in the feminist work of the 1970s and 1990s. The insistence that even seemingly impersonal abstraction is imbued with personal identity or personal feelings, for everyone, men included. The way that craft kept resurfacing, insisting on parity and also a mutual exchange with painting.

The book begins in the 1950s, with the groundbreaking Tibor de Nagy Gallery “posse.” How was that gallery unique? What impact did it have on the generations that followed?

It was unique as the reflection of its owners and their circle of friends and patrons. There was a sensibility and taste that was imaginative, open, and aristocratic in a way—intense and fantastic. It was not partisan in the rather tedious debates of the time about the modern versus the American, but perhaps legible as a gay, cosmopolitan sensibility. The gallery showed young moderns, but also decorative craft and beautiful historical objects. As far as its impact, it exhibited the work of women and gay male artists not always welcomed elsewhere, and championed literature as well as art. That was particularly important for the next generation, including people like Joe Brainard.

In 1961 Morris Louis famously said Frankenthaler was a “bridge between Pollock and what was possible.” In 2013 Mary Weatherford said, “If anyone decides to make stain paintings, even now they have to consider Frankenthaler.” How is the way that contemporary artists embrace Frankenthaler’s legacy comparatively similar to or different from the way that the artists of the 1960s Color Field movement responded?

That Louis quote is a bit of a backhanded compliment—it turns her into a midwife for history, rather than an inventor. That aside, the Color Field section of the show and the book is really different from the others: it evidences a narrowing, a critical orthodoxy, however strong the art itself. This is art that is made, to a certain extent, in the image of Clement Greenberg’s take on the meaning of color and material in painting, reducing it to purely optical or formal concerns. The other artists in the exhibition pick up the diversity, the permissiveness, and the social content of the 1950s, imbuing the stain with sex, psychology, and cultural reference.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s artists became more political, even sometimes identifying as feminists or activists. This is distinctly different from the earlier generation of women artists such as Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, and Joan Mitchell, who bristled at the idea of being called a feminist. How do you see these divergent subjects as connected?

That earlier generation of women artists was

not given the option of being feminists—and, even later in life, many were not interested in embracing that identity when it was on offer. Nonetheless, they faced the same issues as later generations, and enacted some of the same adaptations and solutions: playing both at femininity and masculinity as artificial roles, speaking to each other in private in a different manner than in public speech, and letting their work be filled with their own, unnamed sensibility. Female artists today are more likely to be able to say things out loud, but perhaps still run similar risks in the media and popular conceptions—being pinned down by categorical thinking about gender and identity.

In 1991 Deborah Kass told a reviewer, “We’re in the middle of the worst recession since the ’70s,” adding, “women and people of color are getting attention. . . . It doesn’t cost anything to pay attention.” Do you feel that there was a shift in the 1990s that allowed a wider audience access to artists otherwise less recognized?

Yes, but it didn’t go far enough. The backlash against the infuriatingly shorthand “political correctness” for parity for women, people of color, and the full range of sexual identity really kicked in. It is only now that these demands for equality are back, full force, and significantly, institutions are being forced to begin addressing those demands.

There is a chapter in the book called “The Men’s Room.” What role have male artists had in continuing this legacy?

Men are, of course, as subject to gender identity as women are—theirs only seems invisible because it is the “normal” or dominant kind

of subjectivity. The men in the show, like the women, play with socially determined meanings of masculinity and femininity, trying different roles and transgressing social expectations. The men sew, they fail to control their material, they emote, they display their sexuality, they craft.

Does ambition clash with gender in this book? Has the relationship between gender and ambition changed since the 1950s?

Amy Sillman really gets this in her essay for the book, “House of Frankenthaler.” She recognizes in Frankenthaler a quality that she herself struggles with, the ability to make hugely ambitious and risky gestures with a confidence and authority—a lack of anxiety about the consequences and the details—that seems reserved for men in this culture. Putting that confidence together with the “feminine” is an amazing thing.

If there could be only one thing that you could communicate through this exhibition and publication what would you want it to be?

The fact that the history of art is always a social history, never just a history of style, and the enormously complicated nature of personal identity that exists in each and every work of art.